VC is the Super Hero of Yale's Endowment Portfolio

APRIL 16TH, 2019

I oftentimes find myself pitching venture capital as an asset class. The easy pitch is 'look at what David Swensen has done with the Yale endowment'. That said, think it's important to understand the characteristics of the VC asset class that has largely driven Yale's success relative to its peers, and I'm going to explain how I think about the VC asset class in this post.

Let's start with fund-level time horizons, hold periods for portfolio companies and cashflows to venture capital fund LPs.

One feature of VC that is often surprising to potential LPs is that a venture fund will likely “call” LP capital commitments over a 4-6 period instead of entirely up-front. At Brightstone we tell LPs to plan on a call of 20% of their total capital commitment per year over a span of five years. As a fund manager, this is important because sticking to this timeline causes our fund to be diversified over time- i.e. if we'd called and invested our vintage 2013 fund in 2013 and 2014, we would have missed entire sectors (VR/AR, Blockchain, Gene Editing, Organoids, etc.) that didn't exist until the later years of our planned five-year investment period.

The five year call schedule introduces cash flow benefits to LPs as well. The most significant benefit is that until a VC fund has identified an investment opportunity, LPs get to invest their capital elsewhere. Capital that will be called in years 2-5 can generate returns in other asset classes prior to being called by the VC fund. If an investor commits to a $1m position in a VC fund and earns 6% on uncalled capital over the course of a five-year call schedule they'll earn $144k on uncalled funds. This property is unique to venture capital and builds in a return buffer that de-risks the LP's capital commitment to the VC fund.

So, LP cash calls are fairly predictable and have advantageous characteristics relative to other asset classes. Great. What about LP cash distributions? When can LPs expect to receive distributions from the VC fund? This question is more difficult to answer, but we can look at broad industry stats to give us some idea.

As we can see, the average time to exit stands somewhere around 6 years from the time a company raises its first VC round. At Brightstone, we try to blend our portfolio such that in the early years of a fund, we invest in later stage opportunities with a chance to exit in years 3-4 of the fund's life-cycle. These investments still have to hit our stringent IRR benchmarks, which makes them difficult to find, but they're out there. Thus, we plan to make our first distributions in years 3-4 of our fund's life-cycle, with significantly larger distributions coming in years 5-10, as the majority of our portfolio companies reach maturity.

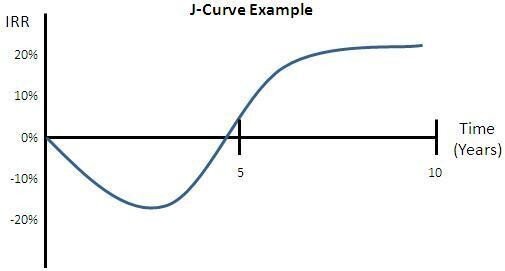

This pattern of capital calls and distributions results in what's known as the VC J-curve.

The J curve is a reference to how capital calls/distributions are realized over the life of a VC fund. The J-curve pattern results in a number of benefits for VC LPs. In the early years of a VC fund, LPs experience a significant tax advantage. Funds are pass through entities so losses in early years pass through as tax deductions for LPs. Investors may see big tax advantages or deductions early on in a fund, which they can apply to gains they are seeing from elsewhere in their portfolio- an under discussed diversification benefit of investing in VC as an asset class.

One last note on taxes, even in later years, gains are typically protected by what is known as Qualified Small Business Stock. If the fund purchased equity in portfolio company before the company has gross assets of $50M or more and the fund holds the equity for more than 5 years, gains up to 10X cost basis, or $10M for each LP, are shielded from federal income tax.

The next question I usually get asked is- ok, but what does the IRR look like once the fund has realized its investments? Good question- glad you asked! In later years (years 3-10, per the discussion above), VC funds begin to realize returns when portfolio companies have exit events. This is where things really get interesting if you look at historical data. early-stage VC as an asset class has historically outperformed other major asset classes over nearly every time horizon.

An important caveat here is that these are indexed VC numbers, and VC is a top quartile (or top decile) business. The top 25% to top 10% of VC funds consistently post return numbers that dwarf the numbers outlined in the chart above. As an example, First Republic used Preqin data to issue a report recently which showed our vintage 2013 Fund I as a top decile fund for both Micro VC and general VC funds for 2007-2015 vintages. The same Preqin data shows that as of the end of Q2 2018, our Fund I is the number three performing 2013 vintage fund in the country, based on its then current IRR of 42.0%. Obviously, our BVC Fund I performance dwarfs the indexed VC performance reflected in the chart above, but even the indexed performance is better than almost every other major asset class.

While it's important to understand the advantages of VC as an asset class- capital call timeline, tax advantages, overall return advantages- it's also important to take a step back and look at how VC impacts your overall portfolio. An important consideration here is what adding VC to your portfolio does to its risk profile. In order to asses this, we need to know the relative correlations between all of the assets in an investor’s portfolio.

This data is important. You can actually de-risk your overall portfolio by adding VC to your portfolio. In particular, you should be looking for low or negative correlation to your other asset classes. By way of example let's look at Large-cap equities- if you owned Medallion Financial Corp (NASDAQ: TAXI) and Uber (via a VC fund) you made out O.K.

Its also important to think about VC as a hedge against short term market movements and longer term recessionary forces that negatively impact public markets. VC is largely insulated against such forces. Looking at the current crop of IPOs, Uber, Pinterest, AirBnB, Slack, WhatsApp, WeWork, Twilio, Instagram, Snapchat, and many of the other breakout VC successes of the last 10-12 years were founded in the recessionary environment of 2008-2010.

Tying that all together- for the right profile of investor, VC is a must-have in your portfolio. VC is not for everyone- LPs must have the ability to be comfortable with making an investment in a fund where their capital will be hard to access for potentially 10+ years. LPs must have the ability to fund capital calls over the first five years of the fund's life cycle. That said, LPs who meet these conditions should strongly consider investing in the VC asset class. The benefits in terms of return performance, tax advantages and portfolio de-risking cannot be overstated. The Yale endowment which has been run by David Swensen since 1985 was one of the earliest institutional investors to recognize the benefits of the VC asset class. The Yale endowment's 20-year time weighted return on their VC portfolio is 24.6%, outperforming all of the other asset classes in their portfolio, while also generating the tax and de-risking advantages discussed above. As a result, Yale recently announced that almost a fifth of their endowment will be allocated to VC going forward. This reflects the confidence that one of the most-watched institutional investors in the United States has in VC as an asset class. Based on the reasons discussed above, it's not hard to see why.